作者:

Granda, Michael Supe

As the turbulent 60's began to fade into the calmer 70's, a coterie of young singers, songwriters, musicians, artists, and poets began to congregate, musically on the stage of The New Bijou Theater - the Springfield, Missouri nightclub that would become the loose-knit group's home. What started as an informal weekly gathering, quickly morphed into a formal band. Dubbed the Fami...

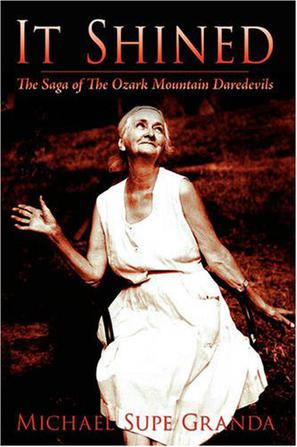

As the turbulent 60's began to fade into the calmer 70's, a coterie of young singers, songwriters, musicians, artists, and poets began to congregate, musically on the stage of The New Bijou Theater - the Springfield, Missouri nightclub that would become the loose-knit group's home. What started as an informal weekly gathering, quickly morphed into a formal band. Dubbed the Family Tree, they became a favorite of the local counter-culture, as well as a continuation of the tradition-rich, Springfield music scene - which, until recently, included the Ozark Jubilee (the nation's first televised country music show). Though unprofitable at the time, they stuck to their guns and their original songs. When a rough tape of an early Bijou gig caught the ear of music mogul, John Hammond, it culminated in a 26-song studio demo, which caught the ear of AandM executive, David Anderle. The group signed with the label, changed their name to its present moniker, and whisked off to London to record their debut album under the tutelage of Glyn Johns. The album contained "If You Want to Get to Heaven." Their subsequent album, recorded in rural Missouri, contained "Jackie Blue." Both songs remain staples on 'classic rock' radio. By the early 80's, the Ozark Mountain Daredevils found themselves right where the Family Tree had stood a decade before - in Springfield with no record deal. They did, though, find themselves with legions of loyal fans around the world. Amidst personnel changes, personal turmoils and a cornucopia of tales from the rock-n-roll highway, the next twenty years were spent 'on the road'. Though continuing to write, they could garner little interest among the rapidly modernizing musicindustry - a situation many long-haired, long-named hippie bands of the 70's find themselves in. Their music, though, lives in the hearts of their fans.

It Shinedtxt,chm,pdf,epub,mobi下载

It Shinedtxt,chm,pdf,epub,mobi下载 Griffith葛里菲兹的。2024-06-19 06:11:39

Griffith葛里菲兹的。2024-06-19 06:11:39 Michael神一般的2024-06-28 12:50:17

Michael神一般的2024-06-28 12:50:17 David可爱的2024-06-26 00:05:38

David可爱的2024-06-26 00:05:38 装装°Escape2024-06-11 02:03:32

装装°Escape2024-06-11 02:03:32